All Change is not Created Equal

By Scott Franklin

As organizations face multiple challenges today, the changes necessary to adapt and thrive range from straightforward to highly complex. In evaluating the complexity of a change, there is one variable that is more significant than any other and that is, “how are the people affected?” If people are expected to learn new skills and the change only requires intelligence and hard work, then you are fundamentally implementing a technical change. On the other hand, if the change requires your people to behave differently, break with deeply held beliefs, and/or create new working relationships, then your organization is facing a complex change.

Oftentimes, organizations have difficulty seeing the complexity of a change because they are accustomed to seeing only the technical challenges, usually underestimating the people side of the change. In working with organizations that are undergoing a complex change, one of the initial steps in preparing for the change is to review the changes and identify the people challenges. Identifying the people challenges allows for adequate preparation of a change strategy that will ensure a successful transition.

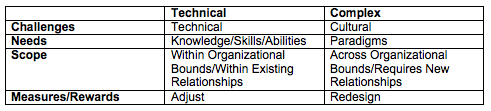

There are four fundamental dimensions to a complex change:

Challenges:

In a technical change, the challenges are essentially technical in nature. They are known problems with known solutions and require knowledge and expertise to solve the issue. In a complex change, the challenges are cultural in nature. In other words, in order to successfully address the challenge, the organizational culture will have to change. The simplest definition of culture is, “the way we do things around here”. If you really want to know an organization’s culture, simply observe the rules of behavior that are taught to the new comers. Some observable characteristics of culture include:

- Accountability – are expectations clear and individuals held accountable for meeting them, or are expectations vague and poorly tracked?

- Discipline – do the individuals in the organization know to meet commitments without continuous follow-up?

- Openness/Honesty – is the truth easy to find or is information guarded and filtered?

- Urgency – is there a culture of sooner rather than later?

- Respect – do people show respect for each other or do they quickly find fault and blame?

Culture changes in organizations are notoriously difficult. In the 15th century, Niccolo Machiavelli observed that:

“It must be considered that there is nothing more difficult to carry out nor more doubtful of success nor more dangerous to handle than to initiate a new order of things; for the reformer has enemies in all those who profit by the old order, and only lukewarm defenders in all those who would profit by the new order; this lukewarmness arising partly from the incredulity of mankind who does not truly believe in anything new until they actually have experience of it.”

This observation is still true. Within organizations, “enemies” appear as organizational resistance and the people who you expect to support the change often hesitate to commit to the new way because they don’t know what it looks like – i.e., “until they actually have experience of it.”

Specifically, one of the most common statements that I have heard in organizations that are looking to transform themselves is, “we have procedures, we just don’t follow them”. A statement like this indicates that an organization needs to change the Accountability and Discipline aspects are their culture. Good changes to be sure, but particularly challenging.

Needs:

In a technical change, the primary needs within the organization are additional knowledge, skills and abilities. In a complex change the organization requires the people to change their paradigms/mental models. A paradigm is a deeply held belief by an individual of what is true or real. Paradigms are formed by beliefs/background, experience, and knowledge. For example, when I was a teenager, New York City was depicted in movies, television, and the news as crowded, dirty and dangerous – not a wholly undeserved representation at that time. Over the past 20 years, tremendous effort has gone into a complete (and successful) makeover of the city – however, my perception of the city did not change much. My wife, however, had a much different view of the city and wanted to take the whole family there. Our girls were 8, 11, and 16 at the time – not good ages for the vision of New York that I had. I reluctantly agreed to the trip and had a wonderful time. I found New York City to be clean, friendly, safe, and exciting and would (and will) gladly go back. New York City was the same city the week before my trip as it was the week of my trip, the only thing that changed was my paradigm – my belief of reality. Until my paradigm changed, I continued to be resistant to the idea of a trip to the city. One of the difficulties in changing my paradigm was that I would have to admit that I was wrong, and had been wrong, about the city for a number of years. Reality had changed faster than my paradigm – and I did not like to admit that I was wrong. Within organizations, we can easily forget that our new vision for the organization will require our employees to give up old paradigms and create new ones.

Scope:

In a technical change, the scope is either within existing organizational bounds or within existing relationships. In a complex change, the scope crosses organizational bounds and requires new relationships. For example, when fully implementing planning and scheduling, a new relationship with operations must be developed and the storeroom must support the system. During the weekly scheduling meetings, operations must cooperate with maintenance to finalize the schedule for the week and then respect the schedule by ensuring the equipment is available as scheduled. This is not an easy change, since operations has most likely been used to running based upon production/shift schedules, not maintenance schedules. In highly functional organizations, it is not uncommon for the plant manager to ask the production manager why maintenance schedule compliance is under target. The storeroom must be capable of kitting parts for scheduled maintenance and even though they may be managed within the maintenance function, the parts kitting process will be a new relationship between the storeroom and the craftspeople.

Rewards/Measures/Incentives:

In a technical change, the rewards/measures/incentives systems are adjusted. In a complex change, the rewards/measures/incentives systems are redesigned. W. Edwards Deming stated:

“Your system is perfectly designed to give you the results that you are getting.”

In other words, to change the results, you must change the system and at the end of the day, the system is optimized around rewards, measures, and incentives. In the previous planning and scheduling example, operations/production owns scheduling of the equipment. If the operations manager is not held accountable for maintenance schedule compliance in some way, then what are the chances that he/she will risk production/shift quota fulfillment to bring down the equipment? If all previous expectations are held in place AND he/she now must add on maintenance schedule compliance, how are inevitable conflicts resolved? Simply piling on requirements may redesign the system – but in a highly reactive manner based upon trial and error. Actively redesigning the system as part of the change requires planning and effort; however, the results tend to be much more sustainable.

When working with organizations that are undertaking a change, the following table (with the above explanations) is helpful to educate leadership on both the level of complexity and the level of change management efforts necessary.

It is unfortunate when an organization assembles the resources and makes an effort to undertake a significant change, only to find out that they failed to adequately account for the complexity of the change and therefore did not apply either the proper or sufficient resources to successfully complete the transition. Change is hard; however, organizations that are becoming proficient at successfully scoping the change and adequately preparing for the appropriate level of complexity are becoming the companies that thrive in today’s environment of constant change.

© Life Cycle Engineering, Inc.

For More Information

843.744.7110 | info@LCE.com